SDGs Interviews: Talking Life Below Water with Yoshihiko Hirata

SARAYA is one of Japan’s leading companies that implement the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This is the thirteenth chapter of SARAYA’s SDG interview series telling the story of those behind SARAYA and how they are working to achieve these goals. In this edition, we spotlight Dr. Yoshihiko Hirata, head of Saraya’s Bio-Chemical Laboratory, and discuss the making of SOFORO, our patented biosurfactant used as a third-generation detergent that keeps the environment safe without sacrificing cleaning power, tackling SDG number 14: Life Below Water.

|

|

Could you tell us how you came to join SARAYA?

It was around 1995 when I was a graduate student at Osaka University School of Engineering, I sent a sample of arthrofactin, a biosurfactant not yet commercially available, to Saraya. My major was fermentation engineering and my research overlapped with the company's research so my professor, who knew Saraya’s former president, introduced me to the company.

A surfactant is a chemical compound, commonly known as a main ingredient of detergent. When it’s added to a liquid, it reduces surface tension and spreads, so it’s used to mix liquids like oil and water, and many others. Normally it’s made from petroleum and not environment-friendly ingredients, but in the case of biosurfactants, it is made with microorganisms using natural ingredients, making it a biodegradable surfactant.

Later, when I was graduating and looking for a job, I came to have an interview with Mr. Shota Saraya, Saraya’s former president. He passionately talked about his aspirations for manufacturing. Somehow, I felt as if it was destiny, so I joined the company.

How did you become interested in research? Tell us about your background.

I was born to a family of three in Higashi Osaka City, an industrial city in the eastern part of Osaka Prefecture. My parents were hardworking tailors operating out of the home, sewing trousers all day every day. Japan’s economy was booming, and people were buying extra trousers to match their suits. I still live around the same area, but it was a lot greener before.

I was a curious child who loved to look at small living creatures like insects, especially mantises and grasshoppers. I would go to nearby parks or the mountains to catch insects and bring them home in my insect cage, giving them green leaves and watching them eat. Every little move they made fascinated me. Since I had no siblings and my parents were so busy working, no one disturbed me.

In the summer, I would go to the beach and spend hours looking for crabs and shrimps between the tetrapods, the concrete structure used at the seacoasts to prevent erosion caused by weather and longshore drift, while other kids were swimming. I would again spend hours looking at those marine creatures, being fascinated with their every move.

When I was a junior high school student, I used to cook instant noodles when I was hungry. And I would wonder where the bubbles came from when the water started to boil in the cooking pan. It wasn't until later that I learned that bubbles were not air, but liquid water turned into gas. I probably wondered "why" more often than others. I may have noticed the presence of science in ordinary things that surrounded me because I always wondered things like “Why does thunder make loud noises?” or “Why is there a rainbow here?” I think my way of thinking hasn't changed at all since then.

I adore nature and it has always been important to me. I’ve never liked the idea that man-made things were causing trouble for the environment and living creatures. I wanted to learn more about the environment and see if I could do something about it. That’s why I decided to study science and majored in fermentation engineering at university.

It was at the university that I encountered the invisible world of microorganisms and learned about the relationship between the microbial world and humans. Fermentation is a positive relationship between microbes and humans, but on the contrary, infectious diseases are a negative one. My research theme at university was about the manufacturing process and functional analysis of detergents produced by microorganisms. I chose this theme because I was amazed to know that microorganisms could make detergents. At the time, I had no way of knowing that my choice of research would lead me to Saraya, never dreaming that I would still be doing research and development on biosurfactants today.

Dr. Hirata, posing in front of SARAYA’s Yashinomi bottles over the years. Photo taken in 2010.

Dr. Hirata, posing in front of SARAYA’s Yashinomi bottles over the years. Photo taken in 2010.

You are now the head of Saraya Bio-Chemical Laboratory, leading their research. Could you tell us about your trajectory?

I joined Saraya in 1997. Soon after, I was assigned to join a research team at Kyoto University, to research the fermentation and production of erythritol, the sweetening ingredient of Lakanto, Saraya's signature natural sweetener. In the end, we were not able to commercialize the production method I researched.

However, during my one-and-a-half-year research assignment, I learned about the differences between corporate research and academic research. At university, you are free to research anything, but at a company, you have to come up with research that is economically rational. I don’t mean that “expensive” is inherently bad since some people would pay a lot to buy anti-cancer drugs. But for erythritol, a sweetener, economic rationality was important as people would not spend a lot of money just to buy a sweetener. During my research at Kyoto University, I got to know great research companions and was able to complete an academic paper, a very important achievement for a researcher. Even now, I still feel the hardships I experienced those days paved the way for me to be where I am now.

I started working full-time at the Saraya Biochemical Research Institute at the end of 1998. It was a new beginning and I was assigned to do all kinds of things I never did before. I was involved with developing powder detergents and enzymatic detergents, the research on the practical application of biosurfactants (now SOFORO), and the development and implementation of medical device cleaning agents (now the MDR - Medical Devices Regulation Division). Today, each of these research projects was successfully implemented and is contributing to society through Saraya. It’s simply so moving and I am honestly happy that it’s happening. There were times when things did not go well and I was heartbroken but I cherished the moment and continued to work hard on my research and manufacturing with the motto of being steady, careful, and persistent. My achievement was accomplished because of the hard work and help of the people around me. I have nothing but gratitude.

SDG number 14 tackles the conservation and sustainable use of oceans, seas, and marine resources. What is Saraya's role in that matter?

Nothing is new about the ever-growing environmental impact caused by human economic activities. I believe that only humans, alias homo sapiens, are the only creatures capable of living in every corner of the earth. Most creatures are limited to live in certain places due to the climate, coexisting without disturbing each other's habitats while sharing the limited resources of the earth. Humans don’t. If we think of human activities done over the air and the sea beside the land, the environmental impact is immeasurable. The power of science made humans accomplish things that they could never do, which from a human race evolution point of view, makes what is happening today almost a miracle. Therefore, we must use this same power of science to create a sustainable society where all living things on Earth can live happily together.

Plastic is often mentioned as a main pollutant of the ocean. It is easy for the mass media to cover because it is visible. However, invisible man-made products are also damaging many organisms. Detergents, unlike plastics, are soluble in water and are impossible to recover. We only can leave it to the healing power of nature. The petroleum-based synthetic detergents we commonly use today were created in the early 1900s, but it has only been about 50 years since they became a daily necessity. We need to carefully observe how this rapid increase in the use of synthetic detergents will affect the environment. In this context, I believe that SOFORO, our third-generation cleaning ingredient that is neither soap nor detergent that we are researching and manufacturing is a great advancement towards a sustainable society.

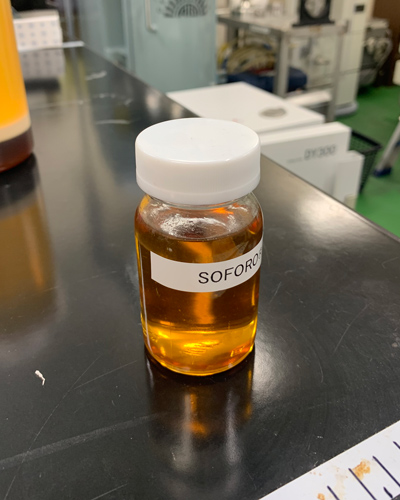

Soforo sample at the bio-chemical laboratory.

Soforo sample at the bio-chemical laboratory.

What is SOFORO, Saraya's third-generation cleaning ingredient?

SOFORO is an organic substance created by yeast, an organism invisible to the human eye. It’s 100% made from biomass and is produced at a normal temperature and pressure, so we don’t have to burn anything to create heat. Furthermore, after use, it is safe for various organisms in the environment. It immediately decomposes into carbon dioxide and water, with carbon dioxide being converted into the next biomass. In other words, it is a natural material that is not only highly functional but also recyclable. You could say its manufacturing method is in harmony with nature.

In terms of function, it has a "non-foaming" characteristic, which is extremely rare among detergents and its washability is sufficiently high, making it suitable for machine washing, such as washing machines and dishwashers.

Our line of Happy Elephant products, as displayed by the SOFORO mark, are made with this bio-surfactant that ensures the biodegradability of the detergent after its use.

Our line of Happy Elephant products, as displayed by the SOFORO mark, are made with this bio-surfactant that ensures the biodegradability of the detergent after its use.

How did SARAYA come to develop SOFORO?

At our Bio-Chemical Laboratory, we have study group meetings once every two weeks to learn about research papers to follow academic trends for a long time. We study various topics, mainly related to hand hygiene and detergent with the concept of natural ingredients.

One day around 2000, someone suggested that we study biosurfactants at one of the study sessions. I was well aware of the difficulty of their practical application because I researched it at university, but I vaguely sensed the potential. I researched a lot of papers, thinking about how to commercialize it, and wrote a proposal.

Competitors may research biosurfactants, but they wouldn't seriously consider their implementation. The reason was simple: it was not economically rational. Especially in detergents, which are particularly inexpensive among many other chemical products, with thousands of surfactants already available. So why should you try to come up with a new surfactant when you already know it’s more costly? I think this is one of the true values of Saraya's principle of “clear stream management” that allows this kind of “odd research themes”. Thanks to that value, the biosurfactant research project began.

By the way, this value is also represented by the Yashinomi detergent formulated by Dr. Kihara, former head of the Bio-Chemical Laboratory, which is so transparent that it’s almost like water. It represents the legacy of Saraya.

What was hard in developing SOFORO? And how did you overcome it?

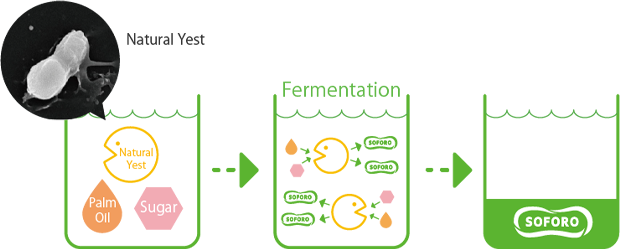

The process of SOFORO creation. Natural yeast, palm oil, and sugar are combined to create SOFORO through fermentation.

The process of SOFORO creation. Natural yeast, palm oil, and sugar are combined to create SOFORO through fermentation.

Our goal was to create a biosurfactant that was of good quality, could be produced stably, and above all, it needed to be economically viable. The research process for SOFORO was a series of trials and errors that took us about two years to find the optimal fermentation conditions, and about a year and a half to find the optimal formula, which we researched at the same time. The time limit given by the company was three years, and we barely managed to meet it!

To make SOFORO, you have to ferment it with yeast, which is a chemical process that breaks down glucose and other molecules in an anaerobic way. Imagine it as the foam part of the beer, as it looks very similar. Fermentation of sophorolipid is done in a jar fermentor. First, glucose (sugar) and oil are added to the water as nutrients for the yeast to grow. Next, the liquid containing these carbon sources is heat sterilized. Bacteria multiply faster than yeast, so you need to sterilize it by boiling and applying pressure at the same time to prevent burning. The yeast extract is then added to the heat-sterilized liquid containing the carbon sources of sugar and oil. Since there is no competition with other bacteria in the heat-sterilized carbon source, it grows rapidly, making the liquid cloudy. Sophorolipid is ready in 1.5 to 2 days.

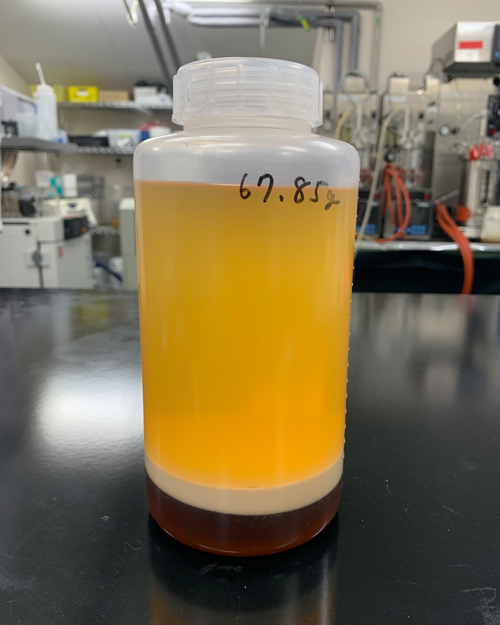

The next step is purification. To extract only sophorolipids from the finished culture medium we apply a downstream processing method. The important points are to completely eliminate oil and sugar during the fermentation process and to control the temperature and airflow to facilitate the separation of the sophorolipids. It took us some time to find that sophorolipids sink better when the pH is in a constant acidic range.

Sample with the creation of SOFORO. The lower layer of liquid is the final result.

Sample with the creation of SOFORO. The lower layer of liquid is the final result.

Once we got to this point, the next challenge was how to separate the sophorolipids. From the fermentation textbooks, we knew that the downstream process would be costly, and that was exactly what happened. We tried various methods such as crystallization and precipitation. Then we experimented with different temperatures, different amounts of oil, different amounts of sugar, and even mixing in different things like yeast extract, fish extract, and beef extract.

Sophorolipid has a higher conversion efficiency than other biosurfactants, with a yield of about 10%. Most other biosurfactants are about 0.1%, so it is a quite efficient biosurfactant.

To come this far, there were many heartbreaking moments, but I was blessed with good research colleagues and my supervisor, Dr. Furuta, who trusted me. I still recall fondly working with Dr. Sugitani and Dr. Igarashi until late at night. It was also helpful that Mr. Sugiura, who was the head of a research institute at a major pharmaceutical company, participated in our research, as he traveled all over Japan to find a suitable partner for us.

When we came to the implementation stage, we had again great new encounters. Managing Director Fukuda and General Manager Daishima of the Consumer Business Division took great interest in our achievements and made many appointments with consumer electronics manufacturers. I still remember how happy I was when our products were adopted by one of the major Japanese electronics manufacturers!

Looking back, Saraya has always had a tradition and culture of aiming for harmony with nature. Researchers could freely conduct research and development with a sense of playfulness, and the company took an interest in the technology, its social implementation, and delivering it to users. The most painful thing for a researcher is when the results of long and painful research are denied. And though some could consider this topic as “strange”, no one opposed this project in Saraya, which probably led to its success.

When I was just a researcher, I was only thinking about the research itself, but now that I am the head of the Biochemical Laboratory, I try to keep the motivations of researchers high and tell my researchers that during their work, they should look also at the benefits for users.

What is the plan like with SOFORO regarding SDG14, Life below water?

Taking advantage of SOFORO's ultra-hypoallergenic properties, we have started to develop products for human use, such as for babies and sensitive skin. We have also discovered emulsification properties, making it suitable for use in cosmetics and topical skin care products. Recently, we have also begun to expand into the field of regenerative medicine.

In other fields, SOFORO was used for decontamination after the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, which caused a lot of secondary damage to nearby residents due to the spread of radioactive materials. SOFORO was adopted as a cleaning agent for roads in radioactive decontamination projects due to its reassuring performance of its non-foaming cleaning power, low impact on aquatic organisms, and high biodegradability.

Our project has won awards, and since last year, we have been participating in NEDO’s (New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization) "Development of Production Technology for Bio-based Products to Accelerate Carbon Recycling", a large-scale national project consisting of more than 50 research institutes, where we will further explore the environmental characteristics of SOFORO scientifically.

You may be surprised to learn that surfactants are used in many different ways. They are used to make cloths, concrete, even pesticides, as it helps improve its stickiness to leaves. Currently, these surfactants are mostly petroleum-derived surfactants, but if we could replace them with biosurfactants, the possibilities would be limitless.

Please give a message to the next generation

There are two important, simple things I learned in my life which would be my message to them: Find a balance between uniqueness and cooperation and never stop thinking.

Improving the sanitation, the environment, and health of the world.

Social

© Copyright Saraya.Co.Ltd 2024 All rights reserved.